If you’re one of the estimated 3 gajillion people who have seen or will see Chris Nolan’s blockbuster movie Interstellar, one thing is already clear to you: this is not a documentary. That means it’s fiction, specifically science fiction, which is how you get the sci and the fi in the sci-fi pairing. So if you go into the movie looking for a lot of scientific ‘gotcha’ moments, let’s stipulate up front that you’re going to find some.

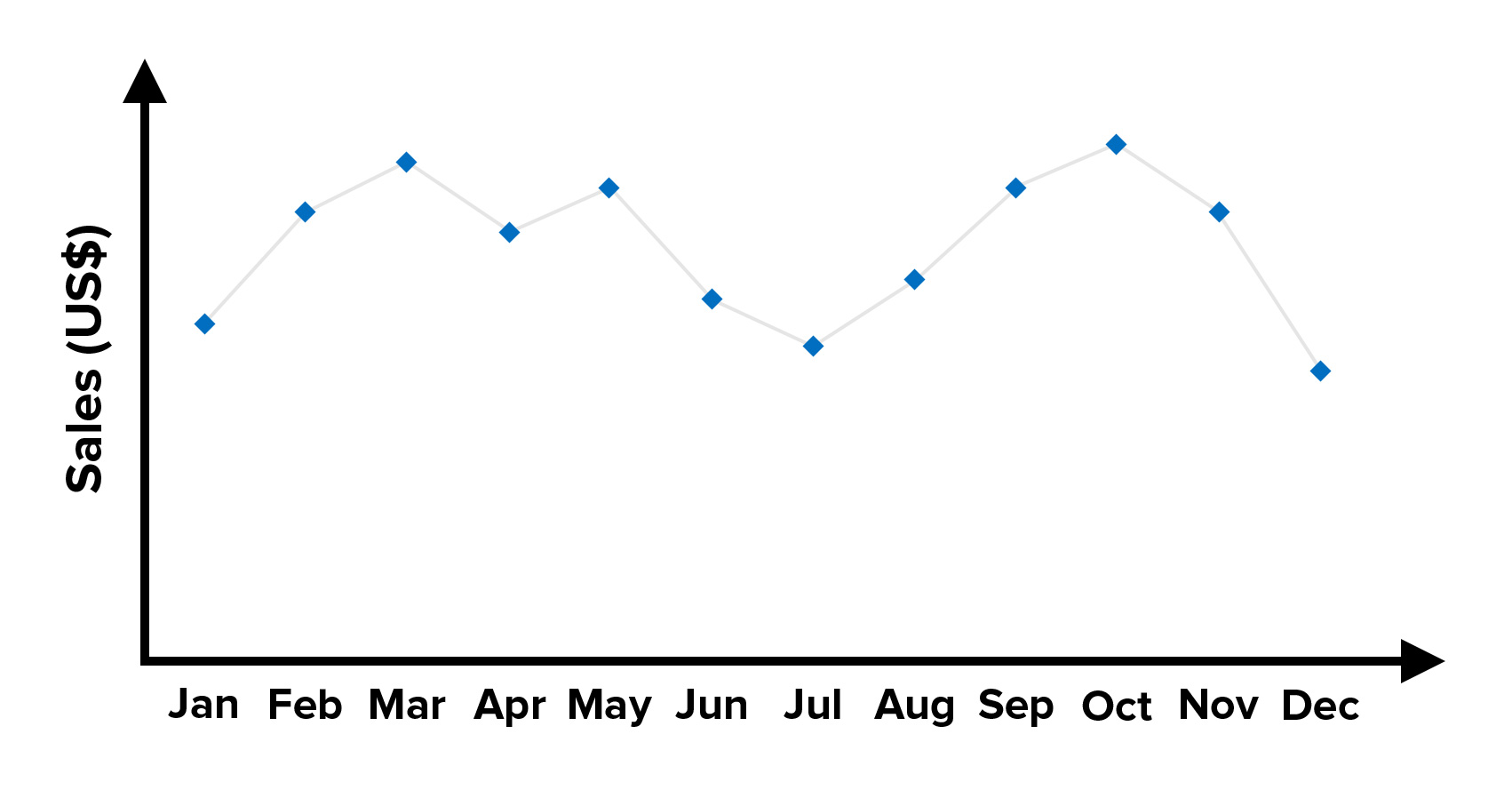

Good Readability. Good resolution. Clear, concise, complete. Font is legible (size, boldness, font choice). Colors enhance the graphic not detract – Reproducibility (quality doesn’t improve upon reproduction – Color blindness and deficiencies. All parts of figure are identified or explained. Key takeaways: Tables and figures are great tools to present sizeable amounts of complex data in a space-saving, easy-to-understand way. Decide when to use a table, a figure, or text depending on the type of data you need to present and what your journal guidelines recommend. Many scientific users will be able to swap palettes in and out pretty much at will, as they will be generating the code to plot their figures. Often, they can even create their own palettes. There are examples in R, python, matlab etc. What distinguishes a scientific figure from other graphical artwork is the presence of data that needs to be shown as objectively as possible. A scientific figure is, by definition, tied to the data (be it an experimental setup, a model, or some results) and if you loosen this tie, you may unintentionally project a different message than intended.

That said, part of Interstellar’s considerable appeal is that it does go heavy on the science part of things. Nolan enlisted Caltech cosmologist Kip Thorne as the film’s technical adviser, and Thorne kept a whip hand on the production, ensuring that the storyline hewed as closely as possible to the head-crackingly complex physics that govern the universe.

So where did Interstellar play it absolutely straight and where did it take the occasional narrative liberty? Here are a few of the key plot points and the verdict from the scientists (warning, there may be spoilers ahead):

1. A worm hole could open in space, providing a short cut from one side of the universe to the other. Verdict: Mostly true

Worm holes are a pretty well-accepted part of modern cosmology and it’s Thorne’s theorems that have helped make them that way. The idea is that if you think of space-time less as a void than as a sort of fabric—which it is—it could, under the right circumstances fold over on itself. Punching the necessary holes in that fabric so that you could make your universe-transiting trip would be a bit more difficult. That would require what’s known as negative energy—an energetic state less than zero—to create the portal and keep it open, says Princeton cosmologist J. Richard Gott. There have been attempts to create such conditions in the lab, which is a long way from a real wormhole but at least helps prove the theory.

One bit of license the Interstellar story did take concerns how the wormhole came to be. It takes a massive object to generate a gravity field sufficient to fold space-time in half, and the one in the movie would have to be the equivalent of 100 million of our suns, says Gott. Depending on where in the universe you placed an object with that kind of mass, it could make a real mess of the surrounding worlds—but it doesn’t in the movie.

2. Getting too close to the gravity well of a massive object like a black hole causes time to move more slowly for you than it would for people on Earth. Verdict: True

For this one, stay with space-time as a fabric—a stretched one, like a trampoline. Now place a 500-lb. cannon ball on it. That’s your black hole with its massive gravity field. The vertical threads in the weave of the fabric are space, the horizontal ones are time, and the cannon ball can’t distort one without distorting the other, too. That means that everything—including how soon your next birthday comes—will be stretched out. Really, it’s as simple as that—unless you want to spend some time with the equations that prove the point, which, trust us, you don’t.

3. It would be possible to communicate to Earth from within a black hole. Verdict: Maybe

The accepted truth about a black hole is that its gravitational grip is so powerful that not even light can escape—which is how it got its name. But even physics may have loopholes, and one of them is something known as Hawking radiation, discovered by, well, guess who. When a particle falls into a black hole, the fact that it’s falling creates another form of negative energy. But nature hates when its books are unbalanced—a negative without a corresponding positive is like a debit without a credit. So the black hole emits a particle to keep everything revenue- neutral. Zillions of those particles create a form of outflowing energy—and energy can be encoded to carry information, which is how all forms of wireless communication work. That’s hardly the same as being able to radio down to Houston from within a black hole’s maw, but it takes you a big step closer.

4. It would be possible to survive the leap into the black hole from which you hope to do your communicating in the first place. Verdict: False—except…

Cosmologists vie for the best term to describe what would happen to you if you crossed over a black hole’s so-called event horizon, or its light-gobbling threshold. The winner, in a linguistic landslide: spaghettification—which does not sound good. But that nasty end may not happen immediately. “Most people would agree that a person who jumps into a black hole is doomed,” says Columbia University cosmologist and best-selling author Brian Greene, “but if the black hole is big enough, you wouldn’t get spaghettified right away.” That’s small comfort, but for a good screenwriter, it’s all the wiggle room you need.

5. And finally: Anne Hathaway could move through time and space and help save all of humanity and her hair would still look fabulous. Verdict: Who cares? We wouldn’t have it any other way.

Read next: Watch an Exclusive Interstellar Clip With Matthew McConaughey

Get The Brief. Sign up to receive the top stories you need to know right now.

Thank you!

For your security, we've sent a confirmation email to the address you entered. Click the link to confirm your subscription and begin receiving our newsletters. If you don't get the confirmation within 10 minutes, please check your spam folder.

For your security, we've sent a confirmation email to the address you entered. Click the link to confirm your subscription and begin receiving our newsletters. If you don't get the confirmation within 10 minutes, please check your spam folder. I’ve been covering the science of human goodness, off and on, for almost 10 years. In that time, I’ve seen a dramatic transformation in the way scientists understand how and why we love, thank, empathize, cooperate, and care for each other.

Of course, “goodness” doesn’t seem like a very scientific concept. It sounds downright squishy to many people, and thus unworthy of study. But you can count acts of goodness—and all science begins with counting. It’s the counting that has started to change our understanding of human life.

Good And Bad Scientific Figures Crossword Puzzle

For example, in a study published in the January edition of the journal Mindfulness, psychologists C. Daryl Cameron and Barbara Fredrickson asked 313 adults if they had helped anyone during the previous week. Eighty-five percent said they had—by, say, listening to a friend’s problems, babysitting, donating to charity, or volunteering.